For inspiration

I open windows

Like magazines

I must construct

The ballad

Of the Esplanade

And end up

Being the minstrel

Of my hotel

But there’s no

Poetry in hotels

Even though

They’re Grand Hotels

Or Esplanades

There’s poetry

In hibiscus

In the hummingbird

In the traitor

In the elevator

…

Who knows what

If some day

The elevator

Would bring

Your love

Up here

—from the “Balada do Hotel Esplanada” segment (translated from the

Portuguese by Thomas Colchie) of Mémorias sentimentais do João Miramar

by Oswald de Andrade

╬ ╬ ╬

EMIR RODRIGUEZ MONEGAL called Manuel Bandeira the John the Baptist of Brazilian modernism and Oswald de Andrade its Messiah. One could also say Mario de Andrade and Oswald were its Peter and Paul; but no relation to Mario, it was Oswald who spurred Brazilian modernism on into the forefront, to form a wave that also brought to shore such icons of Brazilian literature as Cassiano Ricardo, Jorge de Lima, Carlos Drummond de Andrade and João Guimarães Rosa. But, soon, Oswald felt something inside him, deep in his soul, hurting from the changes in his country’s government. So, while Bandeira, Mario de Andrade and Drummond de Andrade stormed forward into the limits of modernist aggression and consequent chest-beating like Pope Damasuses during a burgeoning religious enterprise with the aristocracy, Oswald took a different turn of his head towards the plight of the masses. He felt the sublime there instead of in the modernist here, producing as a consequence the landmark “modernist but anti-modernist” novel

Serafim Ponte Grande. Sadly, he later forgot about the necessities of transferring the sublime in his heart onto his Marxist lectures, so that he became boring with social-realist novels and essays stale as entries on library index cards.

╬ ╬ ╬

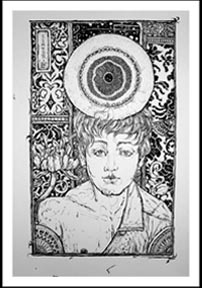

YESTERDAY ON FACEBOOK I saw the painter Marcel Antonio, an expressionist rebel favoring the restraint and melancholic introspection of Raphael, joking around with the budding new artist he—Antonio—is pushing, Gromyko Semper. They were partying over a 2007 Semper montage and parrying semiotic non-significances.

For significance seems to be a non-joke to Semper. On several Facebook discussions, he comes on like an Oswald de Andrade who has dismissed the emptiness of modernist (and even postmodernist) jargon in favor of a more heartfelt theater of intended visual critiques with his art. Like Oswald, Semper seems often to insist on the primacy of his intentions over and above the mirror-gazing habits of modernist and postmodernist classifiers and self-classifiers more interested in their High Art than in a higher Mission.

Antonio, meanwhile, regards the modernist field as an open seedbed for never-ending semiosis, where all levels of meaning can be hunted to please the Mick Jagger-inspired wealthy pop culture that can’t get no satisfaction, aware though he is of Semper’s Derridean hunger for primitive “sublimation”.

I felt I had to crash this party.

╬ ╬ ╬

GROMYKO SEMPER:

GROMYKO SEMPER: circa 2007

Marcel Antonio: “Society is dead,” says Sartre. An abundance of desituationisms concerning Lacanian otherness may be discovered. Thus, if sub-capitalist transitivity holds, the works of Gromyko are modernistic. A number of materialisms concerning a mythopoetical totality exist.

Therefore, the characteristic theme of the works of Gromyko is the role of the artist as reader. Parry states that we have to choose between socialist realism and cultural narrative. But Derrida promotes the use of pre-semanticist sublimation to deconstruct privilege. :D

GS: i dont deny the “modernistic flesh of my works”. however, just as a wolf can dress in lambs’ clothes so can i “deconstruct” imagery, albeit only to symbolically infuse it from its detachments to its purpose, thereby metaphysically reconstructing it to serve its purpose … and i do not like derrida's obscurantism; in fact, the semi-dadaist contextualities of his works are opposite the alternative “modernism” i choose to offer. . . .

MA: Lighten up, dude. Why so serious?

You actually believed there was something sensible in that gibberish nonsense I wrote above? That came from my Ipad, an application called Pomo, a random postmodern ek-ek generator, hahaha! :D

GS: gotcha, i was also using a new program called the anti-postmodern generator generator to be able to respond … hahahahahaha

MA: Hey, Jo! Come out, come out, wherever you are, let's have a funny discussion on this one … :D

Myko, not really kidding; I thought that was a good rebuttal on your part. :D

GS: oh, i forgot that the anti-ek-ek postmodern generator generator is actually implanted in me, so i guess i have to accept the compliments. :-)

MA: Hahaha! :D

GS: there you go, a lively laugh from mr. antonio … i will be uploading the drawing I was telling you about later this noon, by the way. :-)

MA: Dapat lang. Now go play with yourself, I mean, your thoughts. Wala pa si pareng Jo to humor us with Art's gratuitous complexities! :D

(At this point, I was already sharpening my keyboard, ready to crash the virtual terrazzo)

Me: Hey there, you two.

All right, here's my take on it. But first, my prosaic attitude that favors verbosity says: it is possible to take meanings from academic jargon and bring ‘em out into the world and the streets and such blogs as mine that pretends to talk to the nouveau riche, even if only through the not-so-popular language of Harper's or Tik-Tik's horoscope page in English. So, here goes my verbose celebration of modernist jargon:

Despite your claims, I think that work above is mere Pop art, even though by “mere” I mean “wow”. That’s Jim Morrison leaning on the models of DKNY, CK or Penshoppe, right? Heaving towards Peter Saul’s belief in the failure of expressionism to shock but laughing about it, and towards Catholic iconography taunting Greek Orthodoxy for more Byzantine iconoclasm. And that last via a Gutenbergian woodcut or lithograph.

So, Pop art! Especially since it’s a montage.

But wait! Pop art was actually anti-modernist, a vision to ride the most modernist imagery and use it for poetry, kinda like Tarantino using a pre-murder and murder genre sequence to write an ode to both the hamburger and God.

In short, wow.

GS: with classification schema informed on me by talking books out of a not-so-harry-potterish second-hand library of mine, pop/popular art is a gratuitous glorification of societal commercialism/the modern way of idealized life/the american life/mercantile pro-capitalist artisans’ artifacts elevated into a status of art by its warholian assholes. . . . so deriving from this academic jargon one could easily conclude that the piece above by gromyko, which is myself, . . . I wonder, for it does not even tend to glorify any cultural modernism … with irony as weapon for sarcastic conglomeration, the above work attacks societal conditions, relating both sexual perversion and religion into the sphere of human folly via a metaphysical theatre … and pop art is pro modernist, my friend, since it just reconfigures photorealistic imagery into a fatalistic sterile end, in contrast with the symbolic/visionary art spheres of the past generations … but I’ll take the wow first and also the hamburger, to feed my ego and stomach. :-)

MA: Jo: ‘Pop art was actually anti-modernist, a vision to ride the most modernist imagery and use it for poetry’.

Myko: ‘… pop art is pro-modernist … since it just reconfigures photorealistic imagery into a fatalistic sterile end, in contrast to the symbolic/visionary art spheres of the past generations’.

You know what the wise fool said ‘bout jokes being said in half jest?

:D

Me: Well, classification is not exclusive to students of modernism and art historiography, everyone’s a slave of classification. In fact the use of words is the taking advantage of the magic of classification.

It is not so much the words that are to blame for any misunderstanding or under-understanding of their referencing, it is very much the reader of the words that would be at fault. For instance, the word “poverty” would be nothing more than a stale representation of a human condition, that one who has experienced it would have an emotional (one could say full) understanding of the reference, an understanding which would fall short on one who has merely learned the concept from stories told to him by his Dad over cappuccino in the Riviera. And so, a description of artistic activities and intents as either modernist or anti-modernist would have to be approached the same way the word “poverty” is approached.

Now, my understanding of the Warholian intent was one of mimicry or parody of the “commercial glorification” of industrial objects, an intent I can relate to emotionally, being a child of the age of consumerism and the star system, or, as Oswald de Andrade would put it—the age of hotels. It is the age as well of mass-produced irony. In the books

Pop Art: A Continuing History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1990) and

Gardner’s Art Through the Ages (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1980), the authors intimate how Pop confiscates materials from their mass context and isolates them Duchamp-like, combining these imagery furthermore with other objects (say, in Jasper Johns fashion, a Catholic lithograph from the 19th century), all for the purpose of gallery contemplation. Richard Hamilton’s and Roy Lichtenstein's Pop art were another thing altogether, appropriating the stale imprint for poetic or theatrical ends, like yours. Their works, too, by themselves, were acts that peddled irony, sarcasm, and social criticality. And so Pop art, at least by Lichtenstein and Hamilton (and I'd include Peter Saul), was both modernist (for veering away from traditional representation) and anti-modernist (for making sure the art didn't celebrate itself). Warhol’s case was more complex, it was ultra-modernist for making itself as much the subject (bigger than Art itself) as the subjecter; but we might remember that Warhol, too, wanted this I’m-newer-than-you modernist chest-beating to be likewise a corollary subject of his ironies, which would then make him anti-modernist. In fact, that claim—to being a king of parody—makes him a post-modernist, which is just another way of saying “a modernist who parodies his own modernism”. And, so, even Warhol’s classification-crazy and art history-quoting ego was anti-modernist.

Still and all, whatever we say here and no matter what the intentions are, the emotions of the artist and the art are either present or absent according to how the reader approaches the words describing those emotions, classified like the words “hatred”, “anger”, “ennui” and so on, which we can either relate to or not.

So my conclusion is this: all works of art are therefore anti-modernist when they are felt, simply bibliotically classified as mere chest-beaters when they're not. The structuralists and post-structuralists were right, it is always up to the reader of the text more than to the text itself, for the text-maker produceth nothing without the text-reader/feeler, in the same way that a knife does not really wound when it drives into a dead corpse.

Thankfully, your work above, Mr. Semper, under whatever category an encyclopedia would place it, wounds. And that is what I meant by waking up to it with the wound-rhyming word wow.

GS: (retreating somewhat from his Oswald de Andrade-like disgust, tired perhaps) my dear poet de veyra, marcel opened my fourth eye to this interpretative passivity, and i like to say thank you for clarifying it ever more … i enjoyed the slapping of words. . . .

MA: Elegant, Jo, and—as always—things are in their proper logical place.

(He pauses, then poses, pretending to be a teacher with a monocle, Dali-fashion, propping up a backboard and some colored chalks)

Oh yes, I think Myko gets your drift, sir. For instance, Myko paints an apple and perhaps intended to himself that the image shall symbolize something, say the universal idea of Temptation; but Jojo reads the image otherwise, being the viewer and the final arbiter of the image

(he writes the word “final” on the board, so hard that the chalk breaks), and so he comes to the conclusion that the globby marks of marvelous reddish pigment playing on the surface of the canvas(text) and not Myko’s intented meaning(author), is making an impression of looking like a nourishing fruit, but isn't really. So Jojo begins to question the choice of red, and the manner of the strokes, and the exclusion/inclusion of “other” pictorial elements in relation to the flatness of the canvas. He does not entirely dismiss Myko’s self-serving title “Temptation”, but begins to question even the title’s significance to what is already present, or absent, in the work and in the genealogy of painting in general.

In other words, a misreading on Jojo’s part, but certainly not a false one

(he writes the word “not” on the board, making a chalk-screech sound and a chalk-breaking one). Once Myko’s apple painting, which he originally intended to symbolize a central or universal idea of Temptation, leaves the safety of his studio, the painter’s intent dies (Barthes’ famous “death of the author” adage) and the painting ceases to be his idea alone; it is now in fact at the mercy of and opening itself to differing interpretations from both his clamoring fans and disdainful critics. :D

Magritte has already demonstrated this ages-old structuralist idea with his

Ceci n’est pas une pipe painting. ‘Nuff said. :D

╬ ╬ ╬

BUT IN FACT MA digresses to a truism---one that we suspect Myko already knows---and is likely just shy about it, refusing thus to go back to his Pomo opener: “Thus, if sub-capitalist transitivity holds, the works of Gromyko are modernistic.”

MA is shy about it and allows me to finish for him, thusly:

“Derrida promotes the use of pre-semanticist sublimation to deconstruct privilege”: Marxist for questioning privilege, but not so for promoting the sublime. Well, that’s interesting because Oswald could have used the Derridean lesson. For in promoting everything Marxist and anti-bourgeois while throwing everything materialistically modern and anti-bourgeois, Oswald lost the bourgeois necessity of art, the sublime luxury of visions operating like absinthe. Thus he became boring.

GS is wary of that state. Even while knowing his works will be peddled by his sponsor MA for display at Valle Verde parties, banks’ foyers, and hotel promenades, he insists that he shall parry the Warholian image easily classifiable as an index card entry.

MA and I are here to comfort the guy. The reader’s problem is to know the richness within words such as “poverty”, I say, while the artist’s duty is merely to pursue becoming a minstrel of the hotels, bringing love up their elevators, regardless of what happens to his windows being peddled like magazines. [END]

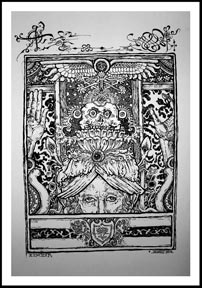

Gromyko Semper

Paracyclopean Mother and child in an interior inspired by Metsu

Acrylic, oil, tempera and ink on canvas, 2010, 24"x30"