photo borrowed from http://www.covershut.com/Television-Covers/43317-Mr-Bean-The-Animated-Series-Grin-And-Bean-It-Disc.html

I DO NOT

know why the Mr. Bean animated series on cable TV’s The Disney Channel is

popular with kids. Maybe it’s because cartoon drawings function like doll or

mascot figures, referencing reality distortedly and thus not realistically,

which makes cartooning the more honest portrayal of The Real qua progressing problematique in our continuing learning. Cartoon people likely come on not like office work problems, but more like crossword or sudoku puzzles we definitely need.

Mr. Bean is an evil but fumbling character with the face of a stereotypical retardate. That personality combine (evil/funny) is probably what makes him amiable instead of despicable, enhanced of course by a recurring atmosphere that declares the "saner world" to be no less evil and corrupt than Bean's funny person.

Now, if by Thomas Hobbes we can admit that man is by nature an evil animal only struggling to be virtuous (for one realized reason or another, which reasons still couldn’t make him selfless), then in the light of a world requiring bits of evil in order to survive Mr. Bean must be to adults a symbol of relative goodness in spite of his evil, if only because a face of sheer innocence or ignorance or retardation or stupidity might be considered exempt from the Hobbesian jungle-smart premise. Yes, Mr. Bean not the merely laughable but the ultimately amiable---amiable because how we wish we could be as innocent as he in both our rancorous mistakes and our cunning!

Or is it the spirit of comic animation as an aesthetic that allows us to forgive evil, being a spirit where evil can get away with it because it, this evil, has become an animation or exaggeration of a hated object, that is to say, has been made demented or stupid or impossible?

Christian authorities mostly stand by this declaration of innocent sinfulness, as being forgivable, in contrast with the knowledgeable's sinfulness as being unpardonable . Apart from that, what are animated beings but beings inferior to our presently perfect real-human selves?

Mr. Bean is an evil but fumbling character with the face of a stereotypical retardate. That personality combine (evil/funny) is probably what makes him amiable instead of despicable, enhanced of course by a recurring atmosphere that declares the "saner world" to be no less evil and corrupt than Bean's funny person.

Now, if by Thomas Hobbes we can admit that man is by nature an evil animal only struggling to be virtuous (for one realized reason or another, which reasons still couldn’t make him selfless), then in the light of a world requiring bits of evil in order to survive Mr. Bean must be to adults a symbol of relative goodness in spite of his evil, if only because a face of sheer innocence or ignorance or retardation or stupidity might be considered exempt from the Hobbesian jungle-smart premise. Yes, Mr. Bean not the merely laughable but the ultimately amiable---amiable because how we wish we could be as innocent as he in both our rancorous mistakes and our cunning!

Or is it the spirit of comic animation as an aesthetic that allows us to forgive evil, being a spirit where evil can get away with it because it, this evil, has become an animation or exaggeration of a hated object, that is to say, has been made demented or stupid or impossible?

Christian authorities mostly stand by this declaration of innocent sinfulness, as being forgivable, in contrast with the knowledgeable's sinfulness as being unpardonable . Apart from that, what are animated beings but beings inferior to our presently perfect real-human selves?

BUT there are moments when we become "inferior" to ourselves, and to others watching us in those moments we become manifestations of saintliness. Perhaps God is an aesthete, then, for after watching way too many movies I’ve come to the

conclusion that man is in his most saintly and beautiful state during those hours of

extreme vulnerability, whether these span a few hours or---as in the

case of the realistic character Robinson Crusoe---a few years. God should win at least a billion best

director awards for giving us these images of saintliness and beauty based on true stories.

photo borrowed from http://www.boaterexam.com/blog/2011/05/real-castaways.aspx

In the movie Cast Away (where the businesslike among us might notice only the production value of putting some all-star cast away for a while in making this one-actor blockbuster of a movie), the hero played by actor Tom Hanks is amiable from the start, even

while at his most cranky-boss frame of mind. It seems like this modern-day

Robinson Crusoe wasn’t exactly unaware of his crankiness as a put-on, consciously allowing underlings to make fun of him so he could get a desired result of projecting amiability on his person and extracting efficiency in others due to this combined amiability and fearsomeness they read in their boss.

Hanks' amiability is of course enhanced a hundredfold by his later isolation in an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. And it’s not just because we love to see people put in spots that weaken them but also because we kind of miss those spots in our lives. In present-day drabness amidst routine, the enjoyment of watching such movies as Cast Away are both a celebration of our good fortunes within our lives’ drabness as well as a vicarious adventure for our repressed-yuppie Survivor-ish desires to be put on the spot.

Hanks' amiability is of course enhanced a hundredfold by his later isolation in an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. And it’s not just because we love to see people put in spots that weaken them but also because we kind of miss those spots in our lives. In present-day drabness amidst routine, the enjoyment of watching such movies as Cast Away are both a celebration of our good fortunes within our lives’ drabness as well as a vicarious adventure for our repressed-yuppie Survivor-ish desires to be put on the spot.

photo from http://www.lindsaybrothers.com/blog/survivor/survivor_thin/

Politicians have an all-too-conscious feel for this PR reality concerning the public’s attraction to the pained. So that when a most hated political opponent dies, they offer their possible presences or sympathies lest the suddenly-softened public steer away from the surviving politicians' hardened souls.

Gossips also suddenly feel both triumphant and sympathetic and afraid when a subject of their hateful judgments begins to cry.

Many women even possess a backhanded sexism towards their own/selves with the recurrent expression of pride in their being tagged "the weaker sex". For instance, in the Philippines, where women can freely wear mini skirts and can run for president, many Filipinas still believe that Real Men don’t fight with their wives but merely allow them to be the emotional and articulate ones. As if a woman’s outbursts are to be equated with a child’s tantrums, best left relatively unattended or reacted to not.

That said, we can now perhaps conclude that humans are quasi-masochistic beings in the sense that they would have to imagine themselves pained in order to qualify for love solicitations. For they know that they, qua subjects to others' eyes, become truer persons in the tension of possible death or during cinematic moments of slow passing away into obsolescence in life.

THE

REASON why we can easily fall for the gibber of actors in real life is because we’ve seen

them play most vulnerable and oppressed characters in fiction or fictionalized cinema that have endeared them to

us. To the public eye, too, artists and poets---once introduced as so---are often seen as likeable soft personae,

despite the swagger or tough look that some of them might display. Rock stars became stars because they dramatized themselves as vulnerable gods forever on the brink of destruction.

A national hero is a mere emblem of some political mythology that we generally can’t really relate to emotionally nor consign significance to as individuals, until we see a movie about the hero’s mistakes and demoralization. Then he becomes a true hero to us, almost a friend.

This reaction doesn’t stop at our impressions upon others. It also extends to our regard for our respective selves. Although many find it hard to admit this truism, still it is not hard to remember that the moments where we have been most proud of ourselves were those wherein we faced a truth, admitted a mistake, or had to wear modesty (with a smile) like a torn suit.

Races-wise, small Asians may prove themselves equal in political or military virility to superpowers’ braggadocio and bullying when they begin to feel comfortable about their difference to the Others, with their shorter penis or body height, thence taking strides forward in the aftermath of this humble acceptance. It’s like the realization that not everybody has to be a tall power forward in a basketball team; one can be a great shooting guard shooting from outside and from underneath. The Japanese, prime examples of Shintoist-Buddhist courage within humility and selflessness, demonstrate/d this pride well, at one time even extending it to arrogance within a different kind of mythical and nationalist humility.

In the case of the social oppression of the individual, he, the individual, usually begins to take strides in a process of freely moving on when he finally concedes to the impossibility of enlightening a majority that is always wrong (or always right for the wrong reasons), proceeding thence to take care of himself and cease and desist from trying to help a public that refuses to be helped.

Stories of a weakened existence, of tension threatening annihilation, or of an Achilles’ heel that took a step towards love, . . . these are human signals that make heroes real, enemies friends, the earlier-despised Malèna in the year-2000 Italian film suddenly adored. Never mind if it’s sometimes too late an acknowledgment, because it couldn’t really be otherwise.

Given all the above, it is perhaps safe to say that the ideal human being would be that one who sincerely acknowledges, or is forced to acknowledge, these human characteristics of constant vulnerability and weakness, acknowledging them even while struggling to control the self’s righteousness or even its recurring greed. Christians call this being reminded of a higher God even while pursuing Mammon.

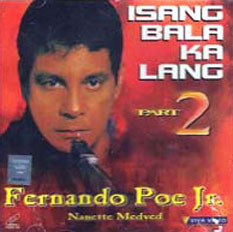

Now, just today, Fernando Poe Jr. died. Before his demise he was declared, by his opponents of course, as a symbol of the Filipino supposedly good, however flawed, but all too willing to forgive all those who stood for greed, larceny, and hedonism, allowing himself be surrounded by these unrepentant male and female whores that comprised his disciples and puppeteers.

A national hero is a mere emblem of some political mythology that we generally can’t really relate to emotionally nor consign significance to as individuals, until we see a movie about the hero’s mistakes and demoralization. Then he becomes a true hero to us, almost a friend.

This reaction doesn’t stop at our impressions upon others. It also extends to our regard for our respective selves. Although many find it hard to admit this truism, still it is not hard to remember that the moments where we have been most proud of ourselves were those wherein we faced a truth, admitted a mistake, or had to wear modesty (with a smile) like a torn suit.

Races-wise, small Asians may prove themselves equal in political or military virility to superpowers’ braggadocio and bullying when they begin to feel comfortable about their difference to the Others, with their shorter penis or body height, thence taking strides forward in the aftermath of this humble acceptance. It’s like the realization that not everybody has to be a tall power forward in a basketball team; one can be a great shooting guard shooting from outside and from underneath. The Japanese, prime examples of Shintoist-Buddhist courage within humility and selflessness, demonstrate/d this pride well, at one time even extending it to arrogance within a different kind of mythical and nationalist humility.

In the case of the social oppression of the individual, he, the individual, usually begins to take strides in a process of freely moving on when he finally concedes to the impossibility of enlightening a majority that is always wrong (or always right for the wrong reasons), proceeding thence to take care of himself and cease and desist from trying to help a public that refuses to be helped.

Stories of a weakened existence, of tension threatening annihilation, or of an Achilles’ heel that took a step towards love, . . . these are human signals that make heroes real, enemies friends, the earlier-despised Malèna in the year-2000 Italian film suddenly adored. Never mind if it’s sometimes too late an acknowledgment, because it couldn’t really be otherwise.

Given all the above, it is perhaps safe to say that the ideal human being would be that one who sincerely acknowledges, or is forced to acknowledge, these human characteristics of constant vulnerability and weakness, acknowledging them even while struggling to control the self’s righteousness or even its recurring greed. Christians call this being reminded of a higher God even while pursuing Mammon.

Now, just today, Fernando Poe Jr. died. Before his demise he was declared, by his opponents of course, as a symbol of the Filipino supposedly good, however flawed, but all too willing to forgive all those who stood for greed, larceny, and hedonism, allowing himself be surrounded by these unrepentant male and female whores that comprised his disciples and puppeteers.

photo from http://www.nndb.com/people/278/000047137/

Macapagal-Arroyo, however, recognizes that today Poe will presently be the people’s good man, having been weakened by Death and been Christianized completely. So the former called him a good man, and so on and so forth, never mind her party’s likely guffaws at the thought of Poe’s wife Susan Roces’ being touted by the opposition as Poe’s possible successor.

This recognition is understandable. After all, politicians also understand that in the eyes of God and humanity we are all Mr. Beans. We are all, both the generally evil and the generally good, sooner or later exposed as but fumbling characters in funny lives, amiable as learning tools and as reminders of ourselves. That inevitability is what will make us to others amiable instead of despicable, on earth as in heaven; that amiability will further be enhanced of course by the cynical atmosphere of a sane world of governance replete with godly ambitions, evil, corruption working us, influencing us. At least while Hobbes' truth remains, God should win at least a trillion best writer-director awards for creating such affable characters, however true the fact is that these characters have at one time or another been friendly to self-appointed gods, those enemies of the poor and oppressed humans, or otherwise been too saintly and iconic for popular appreciation. These characters can't be other than our friendly dolls, being our educational clones.

When the day comes, even the godlike Gloria Arroyo will be an affable Mr. Bean cartoon character. Even if only for a day, as the day's Sesame Street-word of a TV special. [END]

photo from http://maspnational.files.wordpress.com/2009/07/gma.jpg